“I feared not just the violence of this world, but the rules designed to protect you from it, the rules that would have you contort your body to... be taken seriously by colleagues, and ...so as not to give the police a reason. All my life I’d heard people tell their black boys and black girls to “be twice as good,” which is to say “accept half as much.” These words would be spoken... as though they evidenced some unspoken quality, some undetected courage, when in fact all they evidenced was the gun to our head and the hand in our pocket. ” ― Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (2015)

“It was the Lord who knew of the impossibility every parent in that room faced: how to prepare the child for the day when the child would be despised and how to create in the child - by what means? - a stronger antidote to this poison than one had found for oneself.” ― James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Son (1955)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This semester a class of Menlo College literature students are reading both James Baldwin's Notes of a Native Son and Ta-Nehisi Coates' Between the World and Me. After the readings and class discussions they must write a paper identifying one or more shared central themes. The next step, on the path to a final essay, is to compare and contrast the works in terms of style and substance.

This semester a class of Menlo College literature students are reading both James Baldwin's Notes of a Native Son and Ta-Nehisi Coates' Between the World and Me. After the readings and class discussions they must write a paper identifying one or more shared central themes. The next step, on the path to a final essay, is to compare and contrast the works in terms of style and substance.

On the surface, the assignment seems straightforward enough--at least to me. Both works were created some sixty years apart by African American writers/activists. Both works are structured as conversations with and reflections upon the difficulties faced by generations of black men in America. Coates structures his book as a letter to son, and Baldwin's essay is an attempt to understand his father's anger and bitterness--the senior Baldwin having died in 1943, when his son was just nineteen. In each book, the themes of white supremacy, police brutality, rage, violence and despair are maddeningly the same. It's dangerous to be a black man in America.

Here's Baldwin, again, in Notes of A Native Son, reflecting upon his own father's death:

"I had discovered the weight of white people in the world. I saw that this had been for my ancestors and now would be for me an awful thing to live with and that the bitterness which had helped to kill my father could also kill me."

And here's Coates addressing the Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C. earlier this year:

"If you are attempting to study American history and you don't understand the force of white supremacy, you fundamentally misunderstand America."

Over the past few weeks, many students from many different backgrounds have come into the Writing Center asking for help with this assignment. And they are not there to process the passion of Coates and Baldwin. First and foremost, they are challenged by the compare and contrast elements of the assignment--in essence, two assignments in one. Which quotes should the students select to illustrate their thesis and how should they introduce and place the quotes?

But wait--first they need a thesis!

Most started with a statement like:

"Its dangerous to live in a black body in America."

When I reminded them that the works were written six decades apart, some modified the thesis to:

"It's still dangerous to live in a black body in America."

Some began with: The Obama era is clearly over.

Others stated Lincoln's words "all men are created equal" were and are meaningless to black people in America.

As for writing style, most of the students of all backgrounds thought that Coates was the better writer because his direct reporting style was easier for them to understand. Coates writes of "guns to the head, and hands in pockets," while Baldwin has a more poetic language of "antidotes" and "impossiblities"--frequently calling upon the Lord for salvation.

I prefer Baldwin, but I kept out of it.

Still, judging from the quality of their first drafts, there were a lot of students who read the works carefully, and I wanted to ask each of them how reading these words affected them personally. But that's not my role at the Writing Center. Instead I acted as a (hopefully) competent surgeon, inserting commas, rearranging paragraphs, and parsing quotes, even with Coates' and Baldwin's blood running all over the pages.

Would the students even answer my more personal questions? I mean, how comfortable would African American young adults be discussing white supremacy with a white professor with graying hair. And there was every possibility that if we got into it at the Writing Center, somebody was going to say something that hurt somebody, and the Writing Center is, by its very mission, a safe place.

Would the students even answer my more personal questions? I mean, how comfortable would African American young adults be discussing white supremacy with a white professor with graying hair. And there was every possibility that if we got into it at the Writing Center, somebody was going to say something that hurt somebody, and the Writing Center is, by its very mission, a safe place.

The student that I most wanted to talk to turned out to be an eighteen-year-old African American woman who came into the writing center exhausted after pulling an all-nighter. At first, I did not think that any conversation would be possible, let alone editing. She was leaning on the table, her head resting on clasped hands.

"Do you want to come back another time," I asked.

"No", she sighed dramatically. "Let's just do this."

She had nothing written on paper, but quotes were underlined in both works.

"The theme is WAITING."

"Waiting for what?" I asked.

She picked her head up and looked me in the eye.

"Waiting......... to explode!"

"Okay...put that idea into a thesis"

I don't remember enough to record her word-for-word thesis. But the sentences looked something like this:

African Americans get so frustrated and angry but for a lot of reasons they can't react right away. Eventually those who feel most vulnerable and powerless will explode in violence. But when they explode white people will kill them.

So here's what I was thinking.

Someday, was this exhausted young woman going to wake up and explode?

Was it going to happen anytime soon?

Had she seen anyone die because they exploded?

What kinds of injustices would make me explode?

I thought of how I felt watching white supremacists march in Charlottesville chanting "Jews will not replace us."

I didn't share that feeling with her.

She had not asked me to share.

I didn't say to the student, "I know how Baldwin and Coates' rage must feel, because when I was watching the Nazis march in Charlottesville....."

Because I really, truly, don't know her experience.

I'm not even sure I know mine.

What I said was:

"You know, in the first sentence you need to put a comma after the word angry and before the word, "BUT", because the word BUT separates two independent clauses. You also need a comma between the clauses "when they explode" and "white people will kill them."

I hesitantly suggested changing the word "will"--as in "white people will kill them" to a softer "might"--as in "white people might kill them."

I'm not sure if she made that change.

My student left the Writing Center with a well constructed essay. As she was packing up her laptop, I could not resist asking just one question--just one.

"Do you think that Americans will be reading essays like Coates' and Baldwin's sixty years from now?"

"Yes", she answered, without a bit of doubt.

"But maybe next time the writer will be a woman."

"Do you want to come back another time," I asked.

"No", she sighed dramatically. "Let's just do this."

She had nothing written on paper, but quotes were underlined in both works.

|

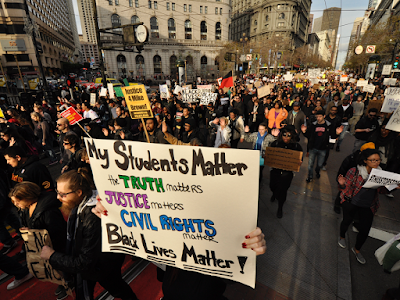

| San Francisco Rally/December 2015 |

"So what do you think the theme is?" I asked, somewhat weary myself. Hers was the fifth Coates/Baldwin assignment I had worked on that day.

"The theme is WAITING."

"Waiting for what?" I asked.

She picked her head up and looked me in the eye.

"Waiting......... to explode!"

"Okay...put that idea into a thesis"

I don't remember enough to record her word-for-word thesis. But the sentences looked something like this:

African Americans get so frustrated and angry but for a lot of reasons they can't react right away. Eventually those who feel most vulnerable and powerless will explode in violence. But when they explode white people will kill them.

So here's what I was thinking.

Someday, was this exhausted young woman going to wake up and explode?

Was it going to happen anytime soon?

Had she seen anyone die because they exploded?

What kinds of injustices would make me explode?

I thought of how I felt watching white supremacists march in Charlottesville chanting "Jews will not replace us."

I didn't share that feeling with her.

She had not asked me to share.

I didn't say to the student, "I know how Baldwin and Coates' rage must feel, because when I was watching the Nazis march in Charlottesville....."

Because I really, truly, don't know her experience.

I'm not even sure I know mine.

What I said was:

"You know, in the first sentence you need to put a comma after the word angry and before the word, "BUT", because the word BUT separates two independent clauses. You also need a comma between the clauses "when they explode" and "white people will kill them."

I hesitantly suggested changing the word "will"--as in "white people will kill them" to a softer "might"--as in "white people might kill them."

I'm not sure if she made that change.

My student left the Writing Center with a well constructed essay. As she was packing up her laptop, I could not resist asking just one question--just one.

"Do you think that Americans will be reading essays like Coates' and Baldwin's sixty years from now?"

"Yes", she answered, without a bit of doubt.

"But maybe next time the writer will be a woman."

No comments:

Post a Comment